ناامیدی در فقدان واژگان رؤیاساز Despair in the Absence of Fantasy‑Building Words

- Jul 29, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Aug 2, 2025

این سطرها را فقط برای سه جفت چشم نوشته بودم، اما حالا با اتکا به مهر همان چشمها، با شما هم بهاشتراک میگذارم. نوشتن این حرفها برای من در ناتوانی من برای نگاهداشتن این طوفان ناامیدی در درونم نهفته است. در سومین روز حملهی اسرائیل به ایران، در لحظههای آشفتگی، با بحران رؤیا مواجه شدم. متوجه شدم که هیچ رؤیایی در هیئت واژه و در سطح خودآگاه برای آیندهی ایران و آن بخش از خودم که به ایران بند است، ندارم. سعی میکنم کمی از این مکاشفه را اینجا توضیح دهم.

جیمز اُرمراد در کتاب رؤیا و جنبشهای اجتماعی (۲۰۱۴) دربارهی کموکیف اثرگذاری متقابل فانتزی یا رؤیا بر جنبشهای اجتماعی مینویسد. او معتقد است که رؤیا از مقدمات ضروری تغییر و تحرک سیاسی است و بههمان اندازه هم ممکن است در بیعملی سیاسی و حفظ نظم موجود مؤثر باشد. او رؤیا را جدای از واقعیت نمیبیند؛ بلکه آن را از پیشنیازهای ساختاری میپندارد که هم به آنچه کنشگران آن را ممکن تصور میکنند، شکل میدهد و هم به اینکه چطور بهدنبال تغییر باشند. از نگاه ارمراد، رؤیا تنها نوعی اتفاق روانی و درونی نیست، بلکه ساختاری ارتباطی است در دل سوژگی سیاسی. رؤیا بهضرورت در تقابل با واقعیت، ناخودآگاه، کنش و جمع تعریف میشود؛ اگرچه که با تمام آنها در رابطهای دیالکتیک است. او معتقد است که رؤیا ممکن است چندین نوع رابطه با این حوزهها داشته باشد، از سرکوب و انکار گرفته تا پذیرش و درگیری انتقادی. او مینویسد رؤیا در سطوح ناخودآگاه (در قالب وهم)، نیمهخودآگاه (در قالب تصویر)، و در خودآگاه (در قالب اندیشههایی که به واژه درآمدهاند) وجود دارد.

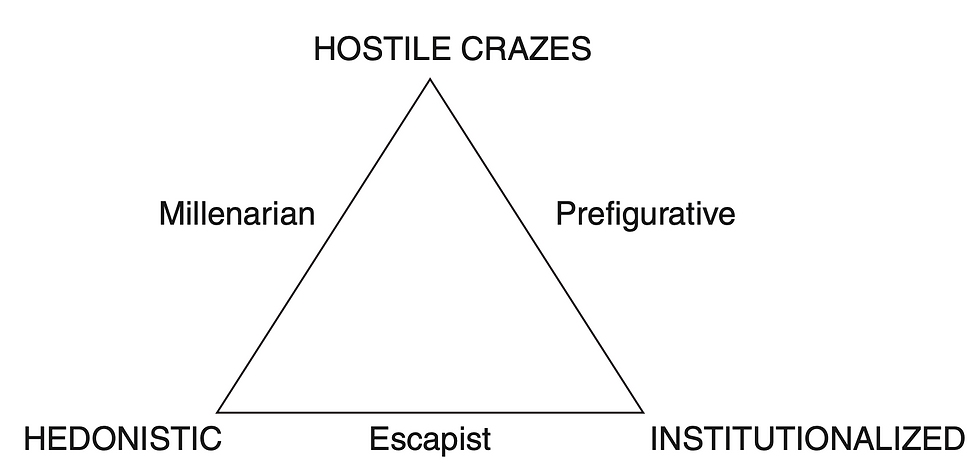

برای استفاده از این چارچوب مفهومی در تحلیل کنشگری، ارمراد شش حالت رؤیا را پیشنهاد میکند. این حالات توصیف میکنند که افراد و گروهها چگونه با میلها، جهان اطراف، و با یکدیگر رابطه برقرار میکنند. رؤیای وهمآلود شامل انکار واقعیت بیرونی و ارضای آنی میل است. آنچه آرزو میشود، بیهیچ سنجشی با واقعیت و بیهیچ امکان ارتباطی با دیگران یا اشیاء دنیای بیرونی، مستقیماً حس میشود. رؤیای خودشیفته نیازمند عمل است، اما این عمل کاملاً در چارچوب رؤیا فیلتر میشود؛ دیگران در این حالت یا ابزارند یا مانع تحقق رؤیا. در چنین موقعیتهایی، سوژهی رؤیاپرداز در امید بازگرداندن جادویی خود به حالت پیشینِ لذت، از ابژههایش بهره میبرد و خود را قادر مطلق میبیند. این در حالی است که رؤیای افسرده، فرد را با واقعیت بیرونی آشتی میدهد و امکان روابط متقابل و مشارکتی را فراهم میکند؛ رؤیا کنار گذاشته نمیشود، بلکه از مرکز به حاشیه میرود و با نگاهی انتقادی حفظ میشود.

ارمراد همچنین سه حالت ترکیبی را شناسایی میکند. حالت قضاقدری که جایی میان رؤیای وهمآلود و رؤیای خودشیفته قرار میگیرد، با روایتهایی دربارهی فروپاشی یا رستگاری در آینده تغذیه میشود، تصاویری که کنشگری انتقادی را ناممکن میکنند. رؤیای گسیخته که جایی میان رؤیای وهمآلود و رؤیای افسرده قرار میگیرد، به انزوای روانی سوژه، هم از رؤیا و هم از کنش سیاسی، منجر میشود. امیدوارکنندهترین حالت، حالت مداخلهگر است که جایی میان رؤیاهای خودشیفته و افسرده شکل میگیرد و در آن، رؤیا و آگاهی انتقادی تعادلی پیدا میکنند. این حالت در تنشی میان حالت خودشیفته و افسرده پدیدار میشود و امکان کنش معنادار را فراهم میکند در حالی که اذعان دارد چنین کنشی ممکن است به تحقق مطلق رؤیا نرسد.

این حالتهای رؤیا با گونهشناسی جنبشهای اجتماعی از نگاه ارمراد تطبیق دارند. جنبشهای لذتگرایانه که با رؤیای توهمی همراهاند، هدفشان خلق فضاهایی احساسی برای لذت یا رضایت موقتی است. در این جنبشها بهندرت تمام کنشهای اجتماعی به تعلیق درمیآید، بلکه اغلب کنشهای معطوف به تغییرند که به تعلیق درمیآید. کنشهای خصمانه، که با حالت خودشیفته مرتبطاند، بر شناسایی یک مانع تمرکز دارند، که اغلب گروهی از «دیگران» است. در این حالت تصور میشود که مانع شناساییشده ابژهی مطلوب یا آیندهی خواستهشده را از دسترس دور نگه میدارد. ابژهای که در مرکز این دشمنی قرار دارد، تنها تا زمانی به کنش اجتماعی منجر میشود که گروهی از دیگران آن را مصادره کرده باشند. بنابراین، این گروه از دیگران بهعنوان مانع لذتمندی بازنمایی میشود. در این جنبشها، خودشیفتگی هر عضو محافظت میشود و سازوکارهای پارانویید–اسکیزوئید بهطور متقابل تقویت میشوند.

جنبشهای نهادیشده، که با رؤیاهای افسرده مرتبطاند، تمایل دارند سیاست را به امور روزمره بدل کنند و میپذیرند که ایدهآلهای آرمانشهری و رؤیاها غیرواقعیاند و واقعیتهای سختِ زندگیِ سیاسی آن رؤیاها را محدود میکند. در چنین جنبشهایی، رؤیا هنوز ممکن است به رسمیت شناخته شود، اما از مرکز سیاست کنار میرود. با وجود محدودیتهای ناشی از نهادهای رسمی، این جنبشها همچنان به ایدهآلهای گستردهتری پایبند هستند و اغلب حس هموابستگی میان اعضا را تقویت میکنند. کنشگران در جنبشهای نهادیشده بیشتر با دیگر اعضا و نهادهای سیاسی همذاتپنداری میکنند و روابط هموابسته را ارج مینهند.

انواع دیگری از جنبشها شکلهای ترکیبی به خود میگیرند. جنبشهای آخرالزمانی، که با حالت قضاقدری پیوند دارند، پیشبینیهایی دربارهی پایان سیستمهای اجتماعی میکنند، چه این پایان هولناک باشد و چه رهاییبخش. باور محرک آنها این است که زمان حال اینچنین است که هست، تنها به خاطر چیزی که هنوز نیامده است. جنبشهای گریزان، که با حالت گسسته مرتبطاند، جهانهایی جایگزین خلق میکنند که در آن آرزوها را در همینجا و اکنون برآورده میشوند. چنین اشکالی از رؤیا ممکن است بهمثابه شکلی از اعتراض عمل کنند، اما در عین حال این خطر را دارند که رؤیای ناآگاهانهی سوژه را نادیده بگیرند.

امیدبخشترین دسته، جنبشهای آیندهنگر هستند که در حالت مداخلهگر عمل میکنند. این جنبشها در تنشی میان کنشهای خصمانه و جنبشهای نهادیشده شکل میگیرند، مبتنی بر یک رؤیا برانگیخته میشوند، در حالی که قادرند از تلاش تمامعیار برای دستیابی صرف به ابژهی رؤیا صرفنظر کنند و جزئیات واقعی موضعی و موقتی آن را بپذیرند. در این فضاها، رؤیا نه سرکوب میشود و نه بهعنوان امری ازپیشمحقق در نظر گرفته میشود؛ بلکه بهصورت افقیِ خارجازدسترس اما هدایتگر حفظ میشود. نکتهی کلیدی آن است که این جنبشها با «دیگران» سر و کار دارند، نه بهعنوان ابزار یا مانع، بلکه بهعنوان افرادی که میتوانند در فرآیند تلاش برای اهداف جمعی دگرگون شوند.

مداخلهی ارمراد چارچوب روانشناختی و سیاسی پیچیدهای برای فهم عملکرد رؤیا در کنشگری ارائه میدهد. مدل او به ما این امکان را میدهد که جنبشها را نه فقط بهعنوان ساختارهای ایدئولوژیک یا راهبردی، بلکه بهعنوان فضاهای عاطفی و رؤیایی و روانی ببینیم. در این نگاه، رؤیا واقعیت را تحریف نمیکند؛ بلکه آن را شکل میدهد.

جریانهای سیاسی ایران، آنها که اغلب در جهانهای مردان ریشه دارند، در سالهای گذشته، بیشتر از جنس کنشهای خصمانه، آخرالزمانی، یا نهادیشده بودهاند. راست و چپ اغلب در تلاش برای حذف دیگریِ مانع و بهرهوری از دیگریِ ابزاری بودهاند. اسلامگرایان یا حتی برخی چپهای منتظر انقلابهای کارگری حال و هوای کنشهای آخرالزمانی از خود نشان دادهاند. گروههای متفاوت اصلاحطلب یا صلحطلب به کنشهای نهادیشده روی آوردهاند. در جنبش زن زندگی آزادی، برخاسته از دل رؤیای زنان در بستری از اندیشهی آزادیخواه چپ، شعاری و رویکردی جان گرفت که شبیه به رویکردهای پیشین نبود. کنشگران پیشرو و فمینیست با رویکردی آیندهنگر کوشش کردند، با بازگشت مداوم به خاستگاه شعار از رویکردهای حذفی گذشته دوری کنند و تمام دیگریهای موجود را در تلاششان برای ایجاد تغییر در وضع موجود در بر بگیرند. آنها کوشیدند با اتکا به شعاری که از دل زبان و گفتمانی برخاسته از بستری متفاوت جان میگرفت، رؤیایی دربرگیر برای آیندهی همگان بسازند.

امین بزرگیان در یادداشتی دربارهی جنگ دوازدهروزهی ایران و اسرائیل با عنوان «آسمان و زمین ایران: نزاع رؤیاها» گوشهای از این رؤیاها را بازنمایی میکند. او پیچیدگی چشمانداز تاریخی رؤیاهای دربارهی ایران را، با افزودن «رؤیای شوم اسرائیل» به تصویر، بیشتر میکند. آنچه اما دوست دارم به این تصویر پیچیده اضافه کنم، این است که معادلات رؤیاپردازی جهان با بازگشت خودکامهها به قدرت دیگر فقط در عرصههای عمومی شکل نمیگیرند که فقط از جنس رؤیاهای جمعی باشند. دیگر مرز مشخصی میان رؤیاهای جمهوریخواهان با رؤیاهای شخص ترامپ نمیشود مشخص کرد، یا میان رؤیای اسرائیلیها و شخص نتانیاهو، یا رؤیای سپاه و جمهوری اسلامی و شخص خامنهای. حالا ما برای فهم اینکه چه رؤیایی دارد در کدام عرصه به کنشهای سیاسی سمت و سو میدهد، باید میان رؤیاهای افراد و جوامع در رفتوآمد باشیم.

از دیگر سو، فروید معتقد است رؤیا تصویری از آینده است، که در واکنش به موقعیت نامطلوب کنونی و مبتنی بر تجربهای مطلوب در گذشته شکل میگیرد. دیگر اینکه، با ارجاع به آنچه نائومی کلاین از مفهوم لنگه (Doppelganger) شرح میدهد، گویی ما رؤیاهایمان را نه فقط در واکنش به وضعیت نامطلوب کنونی که در واکنش به رؤیای دیگری شکل میدهیم؛ تاآنجاکه رؤیای ما شکل صلبی بهخود میگیرد و ما در وضعیت «پوچی جایگزین»(nothing alternative) گرفتار میشویم. بنابراین، ما برای ساختن تصویری رؤیایی از آینده به تجربیات گذشته بازمیگردیم و آن تصویر را بیشتر متأثر از رؤیای دیگری میپروریم تا مبتنیبر نیازی اصیل و درونزاد. اما آیا آنچه از گذشته در اندیشههای ما کاشته شده و فعال مانده است، برای ما رؤیاهای خودآگاه کنشانگیز و پیشبرنده میسازد؟ آیا ما با واژگان تاریخمصرفگذشتهی گفتمانهای سیاسیِ اغلب شکستخورده، میتوانیم رؤیایی برای آینده بسازیم که محرک جنبشهای آیندهنگر باشد؟ آیا زن زندگی آزادی چنین گفتمان و حوزهی واژگانی تازهای برای ما در خود داشت؟ بهعلاوه، آیا رؤیاهای ما حول دغدغهی داشتن نوع خاصی از آینده شکل میگیرند یا صرفاً مبتنی بر تصویری از رفع آنچه در اکنون در جریان است؟ آیا ما آنقدر که راهگشا و پیشبرنده باشد، رؤیایی از جنس خواستن داریم، یا لااقل آنقدر که رؤیای از جنس نخواستن داریم؟

بهگمانم بهرغم غمانگیزبودن درک این نکته، آنچه زن زندگی آزادی را در خیابانها زنده نگه داشت و پیش برد، پیش و بیش از آنکه امکانپذیری رؤیاهای خودآگاه واژهمحور بوده باشد، رؤیاهای نیمهخودآگاه و تنانهی زنان بود، رؤیاهایی که حول تصویری از زندگی بدون حجاب ساخته و به کنش بدنمند تبدیل میشد. گویی رؤیای زن زندگی آزادی در سطح واژگانی از خود این سه واژه فراتر نرفته است؛ نه چون بیمعنا است، چون ادامهی معنادارش هنوز شکل واژه به خود نگرفته است. برای تبیین آلترناتیوی که قرار است زن زندگی آزادی را از رؤیای تصویری نیمهخودآگاه به رؤیای واژگانیشدهی پیشبرندهی کنش اجتماعی آیندهنگر تبدیل کند، بهناگزیر باید به دستگاهی واژگانی و گفتمانی مجهز باشیم که برای ما رؤیایی از آینده بسازد که محتوم به شکست نباشد. این بدین معنا نیست که ما فقط به خلق مفاهیم جدید برای درک وضع بشر در لحظهی اکنون نیاز داریم، که البته این هم درست است؛ بلکه ممکن است به این معنا هم باشد که ما در مکانها و زمانهای زبانی نادرستی در گذشته برای خلق تصویری از آینده جستوجو میکنیم. شاید بهتر باشد به جای تکرار روایتهای غالب قدرتمند تاریخی، دنبال کشف روایتهای ناشنیده و ازدسترفته و گمشدهی گذشته و درک دقیقتر وضعیت کنونی بشر باشیم. شاید برای دستیابی به گفتمانی که در آن ساختن و برساختن رؤیایی ممکن میسر باشد، باید گذشته و حال و آینده را بهشیوهای ازپیشنیاموخته باز بشناسیم. بهگمانم میزان امید ما به آیندهای روشن، یا کمتر تاریک، به امکانپذیری رؤیای خودآگاهِ به واژه درآمده وابسته است. در فقدان چنین رؤیایی، امید از معنا و کارکرد تهی میشود و سوژه به بنبست انگیزه و معنا میرسد. اینگونه است که کنشگران جنبشهای آیندهنگر هم با دستهای خالی از رؤیا و امید، به پیشنرفتن یا فرورفتن محکوم میشوند.

نکتهی دیگر اینکه فهم تقاطعی و منظرمند از جهان، پیچیدگیهایی را نمایان کرده است که در دستگاههای شناختی و رؤیاساز گذشته نادیده گرفته میشدهاند و در واقع شاید آن دستگاهها تا این حد هم پیچیده نبودهاند. فهم تقاطعی ضروری است و بازگشت به جهان پیش از آن هم غیرممکن است. اما بهگمانم برای خروج از پیچیدگیای که به همراه میآورد، ما نه به تظاهر به بازگشت به گذشتهی پیش از آن، که به آهستگی و توجه جمعی و دقیقتر به پیچیدگیهای جدید و کشف راهها و زبانهای تازه نیاز داریم. بهعلاوه، مادامی که ما زبان ساختن رؤیایی ممکن را پیدا نکنیم، امید وهمی فروکشنده و کُشنده بیش نیست. راهحل چیست؟ دقیق نمیدانم. میخواهم به گذشتهی نانوشتهی خودم و اطرافیانم بازگردم و برای تجربههای مطلوب محکوم به سکوتمان واژه بسازم و از رؤیایی بنویسم که شبیه هیچ رؤیای موجود دیگری نیست، اما آنقدر ممکن هست که در من امید و کنش آیندهنگر ایجاد کند. گیج و گنگ و غیرملموس و انتزاعی است؟ میدانم. اگر نبود، در این بنبست نمیبودیم لابد. من از طوفان ناامیدی به سرزمین ناشناختهی بیرؤیایی رسیدهام و این سطور را فقط برای سه جفت چشم نوشته بودم و حالا شما هم آن را خواندهاید.

I had written these lines only for three pairs of eyes, but now, relying on the kindness of those same eyes, I am sharing them with you too. Writing these words stems from my inability to contain within myself this storm of despair. On the third day of Israel’s attack on Iran, in moments of confusion, I faced a crisis of fantasy. I realized that I had no fantasy, in the form of words and at the level of the conscious, for the future of Iran and that part of myself tied to Iran. I will try here to explain a little of this revelation.

James Ormrod, in his book Fantasy and Social Movements (2014), writes about the ways in which fantasy or dream affects social movements. He believes that fantasy is among the necessary prerequisites of political change and mobilization, and just as much, it may also be effective in political inaction and in preserving the existing order. He does not see fantasy as separate from reality; rather, he regards it as a structural precondition that shapes both what activists imagine to be possible and how they pursue change. From Ormrod’s point of view, fantasy is not merely a psychological or inner event but a communicative structure within political subjectivity. Fantasy is necessarily defined in relation to reality, the unconscious, action, and the collective; though it exists in a dialectical relation with all of them. He believes that fantasy may have several kinds of relations with these domains, from repression and denial to acceptance and critical engagement. He writes that fantasy exists at the levels of the unconscious (in the form of phantasy), the semi-conscious (in the form of image), and the conscious (in the form of thoughts that have taken on words).

To use this conceptual framework in analyzing activism, Ormrod proposes six modes of fantasy. These modes describe how individuals and groups relate to their desires, the world around them, and to one another. The hallucinatory modeinvolves denial of external reality and immediate gratification of desire. What is wished for is directly felt, without any measurement against reality and without any possibility of connection with others or with objects of the outside world. The narcissistic fantasy requires action, but that action is completely filtered through the fantasy; others in this state are either tools or obstacles to the realization of the fantasy. In such situations, the subject, in the hope of magically returning to a former state of pleasure, makes use of its objects and sees itself as omnipotent. Meanwhile, the depressive fantasy reconciles the individual with external reality and makes reciprocal and participatory relations possible; the fantasy is not discarded, but rather it shifts from the center to the margin and is maintained with a critical view.

Ormrod also identifies three hybrid or transitional modes. The fatalistic mode, lying between the hallucinatory and the narcissistic fantasy, is fed by narratives about collapse or salvation in the future, images that render critical activism impossible. The dissociative fantasy, lying between the hallucinatory and the depressive fantasies, leads to the subject’s psychological isolation, both from fantasy and from political action. The most hopeful mode is the interventionist one, which emerges between the narcissistic and depressive fantasies, where fantasy and critical awareness find balance. This mode arises in the tension between narcissistic and depressive modes and makes meaningful action possible, while acknowledging that such action may not fully realize the fantasy.

These modes of fantasy correspond to Ormrod’s typology of social movements. Hedonistic movements, associated with the hallucinatory mode, aim at creating emotional spaces for pleasure or temporary satisfaction. In these movements, rarely are all social actions suspended; rather, it is often actions aimed at change that are suspended. Hostile crazes, linked to the narcissistic mode, focus on identifying an obstacle, often a group of “others.” In this state, it is imagined that the identified obstacle keeps the desired object or the wanted future out of reach. The object at the center of this enmity only leads to social action so long as some group of others has appropriated it. Therefore, this group of others is represented as the obstacle to enjoyment. In these movements, each member’s narcissism is protected and paranoid–schizoid mechanisms are mutually reinforced.

Institutionalized movements, associated with depressive fantasies, tend to turn politics into everyday matters and accept that utopian ideals and fantasies are unrealistic, that the hard realities of political life limit those fantasies. In such movements, the fantasy may still be acknowledged, but it is pushed aside from the center of politics. Despite the limitations caused by formal institutions, these movements remain committed to broader ideals and often strengthen a sense of interdependence among members. Activists in institutionalized movements identify more with other members and political institutions and value interdependent relations.

Other kinds of movements take on hybrid forms. Millenarian movements, tied to the fatalistic mode, make predictions about the end of social systems, whether this end is dreadful or liberatory. Their driving belief is that the present is as it is only because of something that has not yet come. Escapist movements, linked to the dissociative mode, create alternative worlds in which desires are fulfilled here and now. Such forms of fantasy may function as a form of protest, but at the same time they risk ignoring the subject’s unconscious fantasies.

The most promising category are prefigurative movements, which operate in the interventionist mode. These movements arise in the tension between hostile crazes and institutionalized movements, and are motivated by a fantasy, while being able to forgo all-out efforts aimed only at attaining the object of the fantasy, accepting instead the actual, local, temporary details of it. In these spaces, fantasy is neither repressed nor regarded as something already achieved, but rather preserved as a horizontal, unreachable yet guiding presence. The key point is that these movements engage with “others,” not as tools or obstacles, but as people who can be transformed in the process of striving for collective goals.

Ormrod’s intervention offers a complex psychological and political framework for understanding the function of fantasy in activism. His model allows us to see movements not just as ideological or strategic structures, but as emotional, dreamlike, and psychic spaces. In this view, fantasy does not distort reality; it shapes it.

Iranian political currents, mostly rooted in men’s worlds, have in past years been more of the hostile crazes, millenarian, or institutionalized type. The right and the left have often sought either to eliminate the obstructive other or to exploit the instrumental other. Islamists, and even some leftists waiting for workers’ revolutions, have displayed the millenarian mode. Various reformist or pacifist groups have turned to institutionalized actions. In the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, born of women’s fantasy within the context of leftist emancipatory thought, a slogan and approach emerged that was unlike previous ones. Progressive and feminist activists, with a prefigurative approach, tried (through continuous return to the origin of the slogan) to distance themselves from eliminative approaches of the past and to include all the existing others in their struggle for changing the present conditions. They sought, by relying on a slogan that arose from a language and discourse born of in a different context, to create an inclusive fantasy for the future of all.

Amin Bozorgian, in a note on the twelve-day war between Iran and Israel titled “Iran’s Sky and Soil: The Conflict of Dreams,” reflects part of these fantasies. He makes the historical landscape of fantasies about Iran even more complex by adding the “Zionism’s ominous dream” to the picture. What I would like to add to this complex image is that the equations of fantasy-making in today’s world, with the return of autocrats to power, no longer take shape only in the public arena or only as collective fantasies. One can no longer clearly distinguish between the fantasies of Republicans and Trump’s personal ones, or between the fantasies of Israelis and Netanyahu himself, or between those of the IRGC and the Islamic Republic and Khamenei himself. Now, in order to understand what fantasy is guiding political actions in which arena, we must move back and forth between individual and collective fantasies.

On the other hand, Freud believes that fantasy is an image of the future, formed in reaction to an undesirable present and based on a desirable past experience. Furthermore, referring to what Naomi Klein explains of the concept of Doppelganger, it is as if we form our fantasies not only in reaction to the current undesirable conditions but also in reaction to the fantasies of the other (so much so that our fantasy hardens into a rigid form and we get trapped in a state of “nothing alternative”). Therefore, in building a fantastic image of the future, we return to past experiences and cultivate that image more under the influence of the other’s fantasy than on the basis of an original, internal need. But does what has been planted in our thought from the past and has remained active create for us conscious, action-generating, progressive fantasies? With the outdated vocabulary of often failed political discourses, can we build a fantasy for the future that would drive prefigurative movements? Did “Woman, Life, Freedom” contain such a new discourse and vocabulary for us? Moreover, do our fantasies form around the concern of having a particular kind of future, or merely on the basis of the image of removing what is going on in the present? Do we have, as much as would be leading and progressive, a fantasy of the kind of wanting, or at least as much as we have fantasies of the kind of not-wanting?

I think, despite how saddening it is to realize this, that what kept “Woman, Life, Freedom” alive and moving forward in the streets was (before and more than the feasibility of conscious, worded fantasies) the semi-conscious and embodied fantasies of women, fantasies built around the image of a life without hijab, which turned into bodily action. It is as though the fantasy of “Woman, Life, Freedom” has not gone beyond the level of words of these three terms; not because it is meaningless, but because its meaningful continuation has not yet taken the form of words. To articulate the alternative that is to turn “Woman, Life, Freedom” from a semi-conscious image-like fantasy into a worded fantasy that drives prefigurative social action, we inevitably need to be equipped with a vocabulary and discourse that will build for us a fantsy of the future that is not doomed to fail. This does not mean that we only need to create new concepts to understand the human condition in the present moment, though that too is true; rather, it may also mean that we are searching in the wrong linguistic places and times of the past to build an image of the future. Perhaps instead of repeating powerful dominant historical narratives, it would be better to seek out the unheard, lost, and forgotten narratives of the past and to have a more precise understanding of the current human condition. Perhaps in order to arrive at a discourse in which the making and constructing of fantasy is possible, we must re-recognize past, present, and future in an as-yet-unlearned way.

I think the extent of our hope for a brighter, or at least less dark, future depends on the feasibility of the conscious fantasy articulated in words. In the absence of such a fantasy, hope becomes emptied of meaning and function, and the subject reaches a dead end of motivation and meaning. In this way, activists of prefigurative movements too, with hands empty of fantasy and hope, are condemned to not moving forward, or to sinking.

Another point is that an intersectional and standpoint-oriented understanding of the world has revealed complexities that had been ignored in past cognitive and fantasy-making apparatuses, and in fact, perhaps those apparatuses were not even so complex. Intersectional understanding is necessary, and returning to a world before it is impossible. But I think, to get out of the complexity it brings with it, we need not to pretend to return to the past, but to move slowly, with collective and more careful attention to new complexities, and to discover new ways and new languages. Furthermore, as long as we do not find the language for making a possible fantasy, hope is nothing but a sinking, killing illusion.

What is the solution? I don’t know precisely. I want to return to the unwritten past of myself and those around me, to build words for our silenced desirable experiences, and to write of a fantasy that resembles no other existing fantasy, but is possible enough to create in me hope and prefigurative action. Is it confused, vague, intangible, and abstract? I know. If it weren’t, we would not be in this dead end. I have come from the storm of despair to the unknown land of fantasy-less-ness, and I had written these lines only for three pairs of eyes, and now you too have read them.

References:

Bozorgian, Amin. “Iran’s Sky and Soil: The Conflict of Dreams.” Naghde Eqtesade Siasi [Critique of Political Economy], 21 June 2025. https://pecritique.com/2025/06/21/آسمان-و-زمین-ایران-نزاع-رؤیاها-امین-بز/.

Klein, Naomi. Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World. First paperback edition. Picadoe, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024.

Ormrod, James S. “Introduction: Fantasy and Social Movements in Context.” Fantasy and Social Movements, by James S. Ormrod, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2014, pp. 1–24. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137348173_1.

Comments